Weekly Review -- The body's psyche

The dynamics of sex and the dynamics of our brain are inextricably linked. One may say that enjoying the former leads to the loss of the latter, but we may as well force ourselves to stop functioning altogether, for we are nothing if not instinctual creatures. The following two films explore human quirks in relation to sexual behavior and the effects that this need has on society as we keep evolving.

Shame (2011) -- Addiction, in its many forms, contributes to the downward spiral of millions of people every day. Sometimes the locus of the urge is externalized, such as food or alcohol, and sometimes it is internalized, as in the case of sex or self-harm. In each instance, there is an inner void that triggers the behavioral pattern. This emptiness and the disastrous power that its consequences wield is the subject of Steve McQueen's sophomore film.

Shame (2011) -- Addiction, in its many forms, contributes to the downward spiral of millions of people every day. Sometimes the locus of the urge is externalized, such as food or alcohol, and sometimes it is internalized, as in the case of sex or self-harm. In each instance, there is an inner void that triggers the behavioral pattern. This emptiness and the disastrous power that its consequences wield is the subject of Steve McQueen's sophomore film.**THIS REVIEW CONTAINS SPOILERS**

Thirty-something New York City executive Brandon Sullivan (Michael Fassbender) is handsome, intelligent and successful. He charms everyone that he comes into contact with and has a comfortable lifestyle, one that does not suffer complacency or attachments. Spending his days shuttling between the expensive loft, the high-paying job and the best Big Apple restaurants, Brandon has the world at his fingertips, but he does not want any of it. He does not need any of it.

What he does want and need is sex. Lots of it, in every way and shape and position imaginable. Underneath his cool exterior, Brandon is a time bomb of rabid self-destruction, caught in a whirlwind of a draining addiction. His existence revolves around Internet porn, masturbation, prostitutes, one night stands, threesomes... the list is endless. When his equally troubled sister Sissy (Carey Mulligan) arrives unexpectedly and disrupts his carefully maintained vacuum, Brandon's life starts disintegrating...

I have been a McQueen fan since I first saw the visceral Hunger, and here his starkly expressive technique crystallizes further. The filmmaker takes the topic from a usually bleak talking point to an erudite study of a man lost inside his purgatory. Once again, the body takes centre stage in his vision. Considering the subject matter, the choice is logical; however, it proves to be a brave and elaborate statement on the themes. Whereas in Hunger the body is the conduit for change and tool of defiance, in Shame its purpose turns into means of survival through reckless, numbing devastation. Seeing Brandon burn out following every inane act of sexual gluttony, seeing him get beaten up and seeing him fall asleep in a fetal position -- all of these images show us the fragility that he not only grapples with, but that he is also metamorphosing into. The body, quite simply, is a filigree mechanism that can be shattered with a single push and Brandon is standing on the edge of strength's precipice.

Another element of note are the flirtation and sex scenes and the nuances that they represent in the context of Brandon's compulsions. I found the way these scenes were shot to be telling of his predicament and state of mind in any given moment, and credit partly goes to fabulous cinematographer Sean Bobbitt. For example, every scene concerning on-line pornography is quick and crisp in its somber tones. The interaction between a character yearning for contact and the ultimate instrument of detachment -- the computer -- cannot be presented in a manner that shows a depth to the exchange, simply because there is none to be shown. On the other hand, Brandon's date with co-worker Marianne (Nicole Beharie) is seen through a warm glow, as though to signify a hint of normalcy that she is capable of infusing into his chaos. The threesome sequence is almost a story unto itself, filmed in a frenetic pace, any potential eroticism dissipating into the realm of mere flesh and the act reaching the peak of insignificance. The shades of grey that McQueen finds in the visual aspect of each encounter add a sense of psychological decorum, bringing the inner conflicts to the surface via unique aesthetic setups.

All of the performances are perfection, but Shame undoubtedly belongs to Michael Fassbender. Uncompromising films like Hunger and Fish Tank have already demonstrated what a fearless actor he was, but Shame takes this trait beyond acting and into the domain of another reality. It might not be easy to appear naked on screen, but it takes a special kind of artistic courage to allow oneself to appear emotionally stripped to the bone. Mining the character for clues, Fassbender uncovers a man ripe with anguish and devoid of hope. The public persona that Brandon hides behind, the restraint that he uses to attempt to mask his compulsion, the rare outbursts and pangs of pain that he endures -- these elements are all pieces of the puzzle that this man represents, even to himself. It is obvious that he has become a shell of whoever he once was, identity replaced with the agony of dependency. The actor's subtle facial expressions, his low-yet-forceful delivery and flow of body language from brash to broken to feverish and back again blend to create one of the most mesmerizing portrayals of a wounded human being in recent cinema.

There is no weak link among the other actors. Beharie is wonderful as Marianne, whose healthy perspective on life and love is no match for Brandon's illness. James Badge Dale is in quasi seducer mode as David, Brandon's boss, who seems to admire and envy his colleague, without a clue that it is the normalcy of his routine that Brandon subconsciously covets. Still, special praise has to go to Carey Mulligan, who is fantastic as Sissy, a vagabond damaged in a manner completely opposite from her brother. This woman is so tangled inside a psychic ache that it renders her obsessive in her neediness. Unable to help Brandon with his problems since she cannot even help herself, Sissy is always in danger of getting lost in a vortex of anonymous despair, which might explain her wish to constantly be the centre of attention. The sibling relationship is complicated and painfully fascinating to watch. Many viewers and theorists have been wondering if the pair was connected through incest. While the film does provide hints, it thankfully lets the audience come up with their interpretation of the bond.

Shame is a contemporary tragedy that places a magnifying lens over our culture of sex, shock and excess. Its protagonist's descent into internal disarray explores what happens to an individual once they are devoured by their desires and isolated by their inability to communicate. It is not a pretty picture and not a pleasant experience, but it does not need to be, since losing the soul never is.

10/10

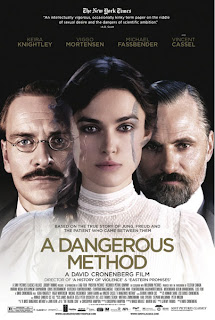

A Dangerous Method (2011) -- The human mind is a labyrinth of mysteries, each one more exciting than the last. Until medical professionals started revealing its riddles, people were not even sure how to view or treat mental illness. Throughout the centuries, most types of disorders were equated with personal rebellion and civil disobedience, with many patients having been placed in institutions and the key thrown away. The situation changed with Sigmund Freud's invention of psychoanalysis, a treatment that delved deep into repressed feelings and blocked memories, thereby beginning to solve the puzzles of the subconscious. David Cronenberg's A Dangerous Method takes a look at this process while examining the lives of the key players, namely Freud, his protégé Carl Jung and Sabina Spielrein, their mutual patient.

A Dangerous Method (2011) -- The human mind is a labyrinth of mysteries, each one more exciting than the last. Until medical professionals started revealing its riddles, people were not even sure how to view or treat mental illness. Throughout the centuries, most types of disorders were equated with personal rebellion and civil disobedience, with many patients having been placed in institutions and the key thrown away. The situation changed with Sigmund Freud's invention of psychoanalysis, a treatment that delved deep into repressed feelings and blocked memories, thereby beginning to solve the puzzles of the subconscious. David Cronenberg's A Dangerous Method takes a look at this process while examining the lives of the key players, namely Freud, his protégé Carl Jung and Sabina Spielrein, their mutual patient.In 1906, Dr. Carl Jung (Michael Fassbender) meets Sabina Spielrein (Keira Knightley), a young Russian woman diagnosed with hysteria. He decides to test his new therapy method -- the "talking cure" -- with her and, in time, the two become collaborators and lovers. Once Jung meets Dr. Sigmund Freud (Viggo Mortensen), who disapproves of Jung's practices and the ethically challenged relationship, a rift starts forming among the three people and it is a question if any of them will leave the conflict unscathed...

The striking thing about A Dangerous Method is its subtlety, particularly considering that the film is directed by David Cronenberg, long known as the master of body horror. It is an intriguing entry in the filmmaker's canon which, so far, has been primarily dedicated to the intricate connection between physical decay and psychological ruin. As much as Rabid and The Fly taint their characters' outward appearances, A Dangerous Method heads in the direction of emotional regeneration and intellectual eloquence. The film is a quiet piece, relying more on the fine points of dialogue and gradations in the actors' delivery than on any bombastic displays; indeed, the closest it gets to introducing corporeal damage is a brisk assault. It takes its time establishing relationships and interweaving their paths within the historical milieu, paying particular attention to the role of sexual attraction in the context of otherwise clinical knowledge.

The standout performances come from the two leads. Fassbender is a chameleon, plain and simple. From activist Bobby Sands in Hunger to Edward Rochester in Jane Eyre to Erik Lehnsherr/Magneto in X-Men: First Class, he disappears into every part and this time it is no different. Jung occasionally gets lost in his own idealism; unafraid of pushing boundaries for the sake of scientific advancement, he often lets his heart rule his head. This trait takes him outside the tenets of professional conduct when he begins his affair with Sabina. As much as he wants to curb his passion, as much as he tries to be who he was before they met, he also starts wondering if he is forsaking himself in doing so. Fassbender does incredible work playing men teetering between sin and redemption, and his Jung is the epitome of a person torn between duty and impulse. Mortensen gives one of his best performances as Freud, whose love for the safety of convention is paradoxical, given that his form of therapy is what turns psychiatry upside down. The two actors' chemistry is palpable, contrasting Jung's youthful enthusiasm and Freud's measured and almost jaded coolness. I would have loved to see more of this interaction, though, and felt that the screenplay had shifted abruptly from the two meeting to the two parting ways.

The rest of the cast do mostly well with their roles. Vincent Cassel is stunningly pained as sex addict Otto Gross. I wish he had more screen time, since his exchanges with Fassbender are insightful and certainly essential to Jung's musings. Sarah Gadon is a picture of tradition as Jung's wife Emma, a woman so tied to social norms that comparing her to the forward thinking Sabina is inevitable. As far as the pivotal female character goes, I do not think that Knightley is able to distinguish between hysteria and histrionics. I find her performance to be more distracting than affecting and wish that she had toned the euphoria down a notch. On another note, I do think that an unknown would have done Sabina more justice, because I believe that the anonymity factor would have contributed to the authenticity of the character's evolution.

There are not too many pieces similar to A Dangerous Method in terms of artistic self-control constructing the rhythm of the narrative. The film puts a twist on the standard drama format with its subdued examination of oppressed instincts and usage of dialogue as analytical tool. Placing an emphasis on the workings of the interior in order to reconcile the workings of the exterior, it pays homage to the legacy of the pioneers it depicts and prompts us to perhaps learn a thing or two from their multifaceted research.

9/10

0 Comments:

Post a Comment

<< Home