Film, life and everything in between

Weekly Review -- The body's psyche

The dynamics of sex and the dynamics of our brain are inextricably linked. One may say that enjoying the former leads to the loss of the latter, but we may as well force ourselves to stop functioning altogether, for we are nothing if not instinctual creatures. The following two films explore human quirks in relation to sexual behavior and the effects that this need has on society as we keep evolving. Shame (2011) -- Addiction, in its many forms, contributes to the downward spiral of millions of people every day. Sometimes the locus of the urge is externalized, such as food or alcohol, and sometimes it is internalized, as in the case of sex or self-harm. In each instance, there is an inner void that triggers the behavioral pattern. This emptiness and the disastrous power that its consequences wield is the subject of Steve McQueen's sophomore film.

Shame (2011) -- Addiction, in its many forms, contributes to the downward spiral of millions of people every day. Sometimes the locus of the urge is externalized, such as food or alcohol, and sometimes it is internalized, as in the case of sex or self-harm. In each instance, there is an inner void that triggers the behavioral pattern. This emptiness and the disastrous power that its consequences wield is the subject of Steve McQueen's sophomore film.

**THIS REVIEW CONTAINS SPOILERS**

Thirty-something New York City executive Brandon Sullivan (Michael Fassbender) is handsome, intelligent and successful. He charms everyone that he comes into contact with and has a comfortable lifestyle, one that does not suffer complacency or attachments. Spending his days shuttling between the expensive loft, the high-paying job and the best Big Apple restaurants, Brandon has the world at his fingertips, but he does not want any of it. He does not need any of it.

What he does want and need is sex. Lots of it, in every way and shape and position imaginable. Underneath his cool exterior, Brandon is a time bomb of rabid self-destruction, caught in a whirlwind of a draining addiction. His existence revolves around Internet porn, masturbation, prostitutes, one night stands, threesomes... the list is endless. When his equally troubled sister Sissy (Carey Mulligan) arrives unexpectedly and disrupts his carefully maintained vacuum, Brandon's life starts disintegrating...

I have been a McQueen fan since I first saw the visceral Hunger, and here his starkly expressive technique crystallizes further. The filmmaker takes the topic from a usually bleak talking point to an erudite study of a man lost inside his purgatory. Once again, the body takes centre stage in his vision. Considering the subject matter, the choice is logical; however, it proves to be a brave and elaborate statement on the themes. Whereas in Hunger the body is the conduit for change and tool of defiance, in Shame its purpose turns into means of survival through reckless, numbing devastation. Seeing Brandon burn out following every inane act of sexual gluttony, seeing him get beaten up and seeing him fall asleep in a fetal position -- all of these images show us the fragility that he not only grapples with, but that he is also metamorphosing into. The body, quite simply, is a filigree mechanism that can be shattered with a single push and Brandon is standing on the edge of strength's precipice.

Another element of note are the flirtation and sex scenes and the nuances that they represent in the context of Brandon's compulsions. I found the way these scenes were shot to be telling of his predicament and state of mind in any given moment, and credit partly goes to fabulous cinematographer Sean Bobbitt. For example, every scene concerning on-line pornography is quick and crisp in its somber tones. The interaction between a character yearning for contact and the ultimate instrument of detachment -- the computer -- cannot be presented in a manner that shows a depth to the exchange, simply because there is none to be shown. On the other hand, Brandon's date with co-worker Marianne (Nicole Beharie) is seen through a warm glow, as though to signify a hint of normalcy that she is capable of infusing into his chaos. The threesome sequence is almost a story unto itself, filmed in a frenetic pace, any potential eroticism dissipating into the realm of mere flesh and the act reaching the peak of insignificance. The shades of grey that McQueen finds in the visual aspect of each encounter add a sense of psychological decorum, bringing the inner conflicts to the surface via unique aesthetic setups.

All of the performances are perfection, but Shame undoubtedly belongs to Michael Fassbender. Uncompromising films like Hunger and Fish Tank have already demonstrated what a fearless actor he was, but Shame takes this trait beyond acting and into the domain of another reality. It might not be easy to appear naked on screen, but it takes a special kind of artistic courage to allow oneself to appear emotionally stripped to the bone. Mining the character for clues, Fassbender uncovers a man ripe with anguish and devoid of hope. The public persona that Brandon hides behind, the restraint that he uses to attempt to mask his compulsion, the rare outbursts and pangs of pain that he endures -- these elements are all pieces of the puzzle that this man represents, even to himself. It is obvious that he has become a shell of whoever he once was, identity replaced with the agony of dependency. The actor's subtle facial expressions, his low-yet-forceful delivery and flow of body language from brash to broken to feverish and back again blend to create one of the most mesmerizing portrayals of a wounded human being in recent cinema.

There is no weak link among the other actors. Beharie is wonderful as Marianne, whose healthy perspective on life and love is no match for Brandon's illness. James Badge Dale is in quasi seducer mode as David, Brandon's boss, who seems to admire and envy his colleague, without a clue that it is the normalcy of his routine that Brandon subconsciously covets. Still, special praise has to go to Carey Mulligan, who is fantastic as Sissy, a vagabond damaged in a manner completely opposite from her brother. This woman is so tangled inside a psychic ache that it renders her obsessive in her neediness. Unable to help Brandon with his problems since she cannot even help herself, Sissy is always in danger of getting lost in a vortex of anonymous despair, which might explain her wish to constantly be the centre of attention. The sibling relationship is complicated and painfully fascinating to watch. Many viewers and theorists have been wondering if the pair was connected through incest. While the film does provide hints, it thankfully lets the audience come up with their interpretation of the bond.

Shame is a contemporary tragedy that places a magnifying lens over our culture of sex, shock and excess. Its protagonist's descent into internal disarray explores what happens to an individual once they are devoured by their desires and isolated by their inability to communicate. It is not a pretty picture and not a pleasant experience, but it does not need to be, since losing the soul never is.

10/10

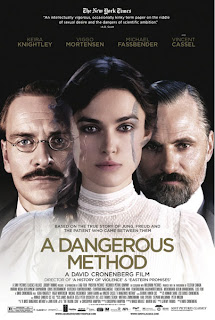

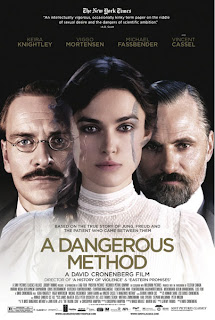

A Dangerous Method (2011) -- The human mind is a labyrinth of mysteries, each one more exciting than the last. Until medical professionals started revealing its riddles, people were not even sure how to view or treat mental illness. Throughout the centuries, most types of disorders were equated with personal rebellion and civil disobedience, with many patients having been placed in institutions and the key thrown away. The situation changed with Sigmund Freud's invention of psychoanalysis, a treatment that delved deep into repressed feelings and blocked memories, thereby beginning to solve the puzzles of the subconscious. David Cronenberg's A Dangerous Method takes a look at this process while examining the lives of the key players, namely Freud, his protégé Carl Jung and Sabina Spielrein, their mutual patient.In 1906, Dr. Carl Jung (Michael Fassbender) meets Sabina Spielrein (Keira Knightley), a young Russian woman diagnosed with hysteria. He decides to test his new therapy method -- the "talking cure" -- with her and, in time, the two become collaborators and lovers. Once Jung meets Dr. Sigmund Freud (Viggo Mortensen), who disapproves of Jung's practices and the ethically challenged relationship, a rift starts forming among the three people and it is a question if any of them will leave the conflict unscathed...The striking thing about A Dangerous Method is its subtlety, particularly considering that the film is directed by David Cronenberg, long known as the master of body horror. It is an intriguing entry in the filmmaker's canon which, so far, has been primarily dedicated to the intricate connection between physical decay and psychological ruin. As much as Rabid and The Fly taint their characters' outward appearances, A Dangerous Method heads in the direction of emotional regeneration and intellectual eloquence. The film is a quiet piece, relying more on the fine points of dialogue and gradations in the actors' delivery than on any bombastic displays; indeed, the closest it gets to introducing corporeal damage is a brisk assault. It takes its time establishing relationships and interweaving their paths within the historical milieu, paying particular attention to the role of sexual attraction in the context of otherwise clinical knowledge. The standout performances come from the two leads. Fassbender is a chameleon, plain and simple. From activist Bobby Sands in Hunger to Edward Rochester in Jane Eyre to Erik Lehnsherr/Magneto in X-Men: First Class, he disappears into every part and this time it is no different. Jung occasionally gets lost in his own idealism; unafraid of pushing boundaries for the sake of scientific advancement, he often lets his heart rule his head. This trait takes him outside the tenets of professional conduct when he begins his affair with Sabina. As much as he wants to curb his passion, as much as he tries to be who he was before they met, he also starts wondering if he is forsaking himself in doing so. Fassbender does incredible work playing men teetering between sin and redemption, and his Jung is the epitome of a person torn between duty and impulse. Mortensen gives one of his best performances as Freud, whose love for the safety of convention is paradoxical, given that his form of therapy is what turns psychiatry upside down. The two actors' chemistry is palpable, contrasting Jung's youthful enthusiasm and Freud's measured and almost jaded coolness. I would have loved to see more of this interaction, though, and felt that the screenplay had shifted abruptly from the two meeting to the two parting ways.

A Dangerous Method (2011) -- The human mind is a labyrinth of mysteries, each one more exciting than the last. Until medical professionals started revealing its riddles, people were not even sure how to view or treat mental illness. Throughout the centuries, most types of disorders were equated with personal rebellion and civil disobedience, with many patients having been placed in institutions and the key thrown away. The situation changed with Sigmund Freud's invention of psychoanalysis, a treatment that delved deep into repressed feelings and blocked memories, thereby beginning to solve the puzzles of the subconscious. David Cronenberg's A Dangerous Method takes a look at this process while examining the lives of the key players, namely Freud, his protégé Carl Jung and Sabina Spielrein, their mutual patient.In 1906, Dr. Carl Jung (Michael Fassbender) meets Sabina Spielrein (Keira Knightley), a young Russian woman diagnosed with hysteria. He decides to test his new therapy method -- the "talking cure" -- with her and, in time, the two become collaborators and lovers. Once Jung meets Dr. Sigmund Freud (Viggo Mortensen), who disapproves of Jung's practices and the ethically challenged relationship, a rift starts forming among the three people and it is a question if any of them will leave the conflict unscathed...The striking thing about A Dangerous Method is its subtlety, particularly considering that the film is directed by David Cronenberg, long known as the master of body horror. It is an intriguing entry in the filmmaker's canon which, so far, has been primarily dedicated to the intricate connection between physical decay and psychological ruin. As much as Rabid and The Fly taint their characters' outward appearances, A Dangerous Method heads in the direction of emotional regeneration and intellectual eloquence. The film is a quiet piece, relying more on the fine points of dialogue and gradations in the actors' delivery than on any bombastic displays; indeed, the closest it gets to introducing corporeal damage is a brisk assault. It takes its time establishing relationships and interweaving their paths within the historical milieu, paying particular attention to the role of sexual attraction in the context of otherwise clinical knowledge. The standout performances come from the two leads. Fassbender is a chameleon, plain and simple. From activist Bobby Sands in Hunger to Edward Rochester in Jane Eyre to Erik Lehnsherr/Magneto in X-Men: First Class, he disappears into every part and this time it is no different. Jung occasionally gets lost in his own idealism; unafraid of pushing boundaries for the sake of scientific advancement, he often lets his heart rule his head. This trait takes him outside the tenets of professional conduct when he begins his affair with Sabina. As much as he wants to curb his passion, as much as he tries to be who he was before they met, he also starts wondering if he is forsaking himself in doing so. Fassbender does incredible work playing men teetering between sin and redemption, and his Jung is the epitome of a person torn between duty and impulse. Mortensen gives one of his best performances as Freud, whose love for the safety of convention is paradoxical, given that his form of therapy is what turns psychiatry upside down. The two actors' chemistry is palpable, contrasting Jung's youthful enthusiasm and Freud's measured and almost jaded coolness. I would have loved to see more of this interaction, though, and felt that the screenplay had shifted abruptly from the two meeting to the two parting ways.

The rest of the cast do mostly well with their roles. Vincent Cassel is stunningly pained as sex addict Otto Gross. I wish he had more screen time, since his exchanges with Fassbender are insightful and certainly essential to Jung's musings. Sarah Gadon is a picture of tradition as Jung's wife Emma, a woman so tied to social norms that comparing her to the forward thinking Sabina is inevitable. As far as the pivotal female character goes, I do not think that Knightley is able to distinguish between hysteria and histrionics. I find her performance to be more distracting than affecting and wish that she had toned the euphoria down a notch. On another note, I do think that an unknown would have done Sabina more justice, because I believe that the anonymity factor would have contributed to the authenticity of the character's evolution.

There are not too many pieces similar to A Dangerous Method in terms of artistic self-control constructing the rhythm of the narrative. The film puts a twist on the standard drama format with its subdued examination of oppressed instincts and usage of dialogue as analytical tool. Placing an emphasis on the workings of the interior in order to reconcile the workings of the exterior, it pays homage to the legacy of the pioneers it depicts and prompts us to perhaps learn a thing or two from their multifaceted research.

9/10

Weekly Review -- Mind's renaissance

The Help (2011) -- Status quo is one of the most difficult things to overcome. The very name suggests stagnancy in the midst of complacency. It always changes the fabric of society for the worse, amplifying the discrepancies between the classes AND the classes themselves, as well as destroying the soul of an individual.Unless that individual is Skeeter Phelan or Aibileen Clark.One of last year's most touching and important films, The Help brings to life a civil rights struggle that has never been presented from the point of view of the women involved. Novelist Kathryn Stockett and filmmaker Tate Taylor document this somber period from the perspective of women uniting against ignorant minds, refusing to back down in the face of injustice and refusing to be bogged down by the past.

The Help (2011) -- Status quo is one of the most difficult things to overcome. The very name suggests stagnancy in the midst of complacency. It always changes the fabric of society for the worse, amplifying the discrepancies between the classes AND the classes themselves, as well as destroying the soul of an individual.Unless that individual is Skeeter Phelan or Aibileen Clark.One of last year's most touching and important films, The Help brings to life a civil rights struggle that has never been presented from the point of view of the women involved. Novelist Kathryn Stockett and filmmaker Tate Taylor document this somber period from the perspective of women uniting against ignorant minds, refusing to back down in the face of injustice and refusing to be bogged down by the past.

Following university studies, the aforementioned Skeeter (Emma Stone) returns to her Mississippi home determined to become a writer. When she gets a job at the local newspaper, she asks her friend Elizabeth's (Ahna O'Reilly) housekeeper Aibileen (Viola Davis) for help with the cleaning advice column that she is working on. Soon, though, Skeeter's focus shifts, as she realizes what kind of treatment the African-American housekeepers are enduring on a daily basis and how her own family and friends are shamelessly contributing to it. She decides to conduct interviews for a book that is going to reveal the racist truth, concealed under the pretense of laws in the segregated South. As Skeeter's preparations unfold, the young woman finds out who she is and who her allies are...Like the rest of the world, I was aware of the American Civil Rights Movement and its inception. I was aware of Rosa Parks' 1955 triumph, the 1963 16th Street Baptist Church bombing and the 1964 Mississippi murders, among other events of the era. This readiness of knowledge did not prevent me from bawling in the film's first fifteen minutes. Frankly, I was in shock at the brutal treatment of human beings that I knew to be far from fiction. Seeing a reenactment while knowing that someone had lived through these situations was a rather disturbing experience, but not more so than the harrowing reality of 1960s America. Watching these ladies strive to remain invisible to the exploitative white families and watching them laugh in the rare moments of joy is a powerful contrast, one that creates the film's gravitas. In general, it is the element of female friendship and bonding that builds the rapport between the on-screen proceedings and the audience. The characters and the battles they fight are richly drawn, taking us on an emotional roller coaster ride. We bear witness to Aibileen's love for Elizabeth's daughter and Celia's outcast status. We cheer on Skeeter's resolve to remain an intelligent, outspoken woman in a misogynistic environment. These representations of virtues conquering transgressions constitute the core of The Help, with the fresh narrative conveying the intricate nature of relationships born within bigotry.The acting complements Taylor's perceptive screenplay. Stone is zeal personified as the spunky Skeeter, who does not let anything interfere with her beliefs and integrity. Octavia Spencer radiates as Minny Jackson, a woman so chronically abused that she has become afraid of hope itself. Viola Davis... wow. What an intense and heartbreaking portrayal of a person who was never given a chance to be whoever she wanted to be. Another standout is Jessica Chastain as Celia Foote, a gentle and misunderstood soul who bonds with Minny and gives her a push to break out of her restrictive life. Howard is also a revelation as the uptight and racist Hilly Holbrook, a woman blinded by her hatred and ill-perceived superiority, while Allison Janney and Sissy Spacek have fantastic supporting turns as Skeeter's and Hilly's mother, respectively. Finally, special mentions must go to Cicely Tyson's Constantine Jefferson. Although the role is small, the character is pivotal for Skeeter's evolution and Tyson does her justice. The actor is able to express more through glances and body language than many other performers might be able to express using pages and pages of script.The Help is a film that invites the audience into its world and does not allow us to make ourselves cozy. Instead, it requests that we reconsider our lives in light of the oppression that it depicts and look at the bigger picture in regard to the manner in which we treat others. Its story is a slice of truth from a thankfully bygone era; nevertheless, it is impossible to forget that merely half a century has passed since these crimes occurred. The film does not settle for preaching the bland excuse of tolerance, but chooses to foster respect, encourage change and wisely remind us that progress still has a long way to go.10/10

Weekly Review -- A matter of lore

Blood and Chocolate (2007) -- I would venture to guess that fantasy was one of the top three most popular cinematic genres at any given time, the other two being horror and family fare. These genres breed fandoms, fill out conventions and spawn fan fiction, all based on the audiences' love of the stories told and characters involved. On the opposite end of the quality spectrum, a fantasy film does not always live up to its potential, which is what happened with this Katja von Garnier adaptation of Annette Curtis Klause's novel.Teenage werewolf Vivian (Agnes Bruckner) has been living in Bucharest with her aunt Astrid (Katja Riemann) ever since her parents were murdered by hunters. Promised by law to the leader of her pack, the authoritarian Gabriel (Olivier Martinez), Vivian's world turns upside down when she meets artist Aiden (Hugh Dancy) by pure chance. Her affection for him and the pressure from the pack soon brings her alliances into question...Right off the bat, I have to praise Kevin Phipps' production design. He utilizes the Gothic ambiance and architectural diversity of the gorgeous Bucharest to the advantage of the story, adding a sense of mystery and anticipation. Unfortunately, the aesthetics of the film are also the best part, glossing over a narrative chock-full of unfinished characters and listless plot development. One cannot help but wonder about what happened with the screenplay. Its starting point was a unique take on the werewolf lore, a tale within which the characters would have had plenty of room to grow. As it is, they are stunted, having been removed from any kind of genuine emotional conflict that the viewer would be able to invest in. Vivian is the figure painted with most detail, but a singular personality does not cinematic relationships make, and Blood and Chocolate offers up some pretty hollow liaisons. The acting is adequate, if a little stilted. Bruckner does what she can with the staccato script, the force majeure that prevents her from delving deeper into Vivien's multidimensional traits. Dancy elicits empathy as Aiden, whose back story could have provided an interesting context had it been examined further. Martinez's performance also suffers from the weak writing, giving us a mere taste of how powerful Gabriel could have been, while Riemann does not have a lot to do as Astrid overall. On a trivia note, fellow "Torchwood" fans will recall Brian Dick's (Rafe) memorable guest appearance as alien Adam on the show. Blood and Chocolate occasionally feels as though someone had decided to cut up the novel and put pieces of it together for the film without looking. The flaws are frustrating, partly because the film ignores its own hints at depth and partly because it wastes its crop of talent in the process, letting itself teeter between imagination and fabrication. A fantasy exists as such for the audiences to lose themselves in. It is a shame when one has to keep peering over their shoulder and not simply enjoy the escape. 5/10

Blood and Chocolate (2007) -- I would venture to guess that fantasy was one of the top three most popular cinematic genres at any given time, the other two being horror and family fare. These genres breed fandoms, fill out conventions and spawn fan fiction, all based on the audiences' love of the stories told and characters involved. On the opposite end of the quality spectrum, a fantasy film does not always live up to its potential, which is what happened with this Katja von Garnier adaptation of Annette Curtis Klause's novel.Teenage werewolf Vivian (Agnes Bruckner) has been living in Bucharest with her aunt Astrid (Katja Riemann) ever since her parents were murdered by hunters. Promised by law to the leader of her pack, the authoritarian Gabriel (Olivier Martinez), Vivian's world turns upside down when she meets artist Aiden (Hugh Dancy) by pure chance. Her affection for him and the pressure from the pack soon brings her alliances into question...Right off the bat, I have to praise Kevin Phipps' production design. He utilizes the Gothic ambiance and architectural diversity of the gorgeous Bucharest to the advantage of the story, adding a sense of mystery and anticipation. Unfortunately, the aesthetics of the film are also the best part, glossing over a narrative chock-full of unfinished characters and listless plot development. One cannot help but wonder about what happened with the screenplay. Its starting point was a unique take on the werewolf lore, a tale within which the characters would have had plenty of room to grow. As it is, they are stunted, having been removed from any kind of genuine emotional conflict that the viewer would be able to invest in. Vivian is the figure painted with most detail, but a singular personality does not cinematic relationships make, and Blood and Chocolate offers up some pretty hollow liaisons. The acting is adequate, if a little stilted. Bruckner does what she can with the staccato script, the force majeure that prevents her from delving deeper into Vivien's multidimensional traits. Dancy elicits empathy as Aiden, whose back story could have provided an interesting context had it been examined further. Martinez's performance also suffers from the weak writing, giving us a mere taste of how powerful Gabriel could have been, while Riemann does not have a lot to do as Astrid overall. On a trivia note, fellow "Torchwood" fans will recall Brian Dick's (Rafe) memorable guest appearance as alien Adam on the show. Blood and Chocolate occasionally feels as though someone had decided to cut up the novel and put pieces of it together for the film without looking. The flaws are frustrating, partly because the film ignores its own hints at depth and partly because it wastes its crop of talent in the process, letting itself teeter between imagination and fabrication. A fantasy exists as such for the audiences to lose themselves in. It is a shame when one has to keep peering over their shoulder and not simply enjoy the escape. 5/10

Weekly Review -- Fighting the bad fight

Green Street Hooligans (2005) -- The male bonding film trend occasionally falls into two categories -- works with a farcical perspective and works involving inspirational sports metaphors. Sometimes a too-cool-for-school cinematic martini such as Doug Liman's Swingers slips through the shallow cracks, and sometimes we get a film like Lexi Alexander's Green Street Hooligans, which tests the spirit of male camaraderie as it braves the elements of a strictly delineated code. When Harvard journalism student Matt Buckner (Elijah Wood) is wrongfully expelled, he travels to London to visit his sister (Claire Forlani) and her family. Soon afterward, he meets her brother-in-law Pete (Charlie Hunnam), who introduces Matt to his firm, an outfit of football hooligans. Entering a secretive lifestyle and finding a place to belong for the very first time, Matt also starts participating in the violence that comes with the territory. What he is not counting on is a rival firm's growing extremism... Right off the bat, I will say that I have never been and will never be able to understand brutality and fanaticism for the sake of anything, let alone a sport. However, do not go into this film expecting bloody barbarians senselessly murdering one another, with the story taking the back seat. Sure, the fights shown are savage, but it is the core of morality and character that drives this narrative, turning it from what might seem like a conventional sports-oriented piece into a tale of unbreakable friendships. The screenplay pays attention to the people inhabiting its pages, never portraying them as cartoonish stereotypes that they could have been; rather, it sees them as complex, fallible, tragic figures. I would have been interested in seeing more of Matt's background with his sister and Pete's with his brother, since the entire context of a football family could have been broadened through the clearer context of the biological ones. The cinematography by Alexander Buono, who had also painted the aesthetics of the fantastically underrated 2003 chiller Dead End, is a perfect fit. Steely and smoggy, it evokes an atmosphere of urban decay and constant surveillance, a real life feeling that is undoubtedly one of the factors contributing to Great Britain's problem of football violence. At one point, one of the characters even refers to Britain as a country under the watchful eye of Big Brother.

Green Street Hooligans (2005) -- The male bonding film trend occasionally falls into two categories -- works with a farcical perspective and works involving inspirational sports metaphors. Sometimes a too-cool-for-school cinematic martini such as Doug Liman's Swingers slips through the shallow cracks, and sometimes we get a film like Lexi Alexander's Green Street Hooligans, which tests the spirit of male camaraderie as it braves the elements of a strictly delineated code. When Harvard journalism student Matt Buckner (Elijah Wood) is wrongfully expelled, he travels to London to visit his sister (Claire Forlani) and her family. Soon afterward, he meets her brother-in-law Pete (Charlie Hunnam), who introduces Matt to his firm, an outfit of football hooligans. Entering a secretive lifestyle and finding a place to belong for the very first time, Matt also starts participating in the violence that comes with the territory. What he is not counting on is a rival firm's growing extremism... Right off the bat, I will say that I have never been and will never be able to understand brutality and fanaticism for the sake of anything, let alone a sport. However, do not go into this film expecting bloody barbarians senselessly murdering one another, with the story taking the back seat. Sure, the fights shown are savage, but it is the core of morality and character that drives this narrative, turning it from what might seem like a conventional sports-oriented piece into a tale of unbreakable friendships. The screenplay pays attention to the people inhabiting its pages, never portraying them as cartoonish stereotypes that they could have been; rather, it sees them as complex, fallible, tragic figures. I would have been interested in seeing more of Matt's background with his sister and Pete's with his brother, since the entire context of a football family could have been broadened through the clearer context of the biological ones. The cinematography by Alexander Buono, who had also painted the aesthetics of the fantastically underrated 2003 chiller Dead End, is a perfect fit. Steely and smoggy, it evokes an atmosphere of urban decay and constant surveillance, a real life feeling that is undoubtedly one of the factors contributing to Great Britain's problem of football violence. At one point, one of the characters even refers to Britain as a country under the watchful eye of Big Brother.

The cast is well chosen. Wood gives an effective performance, depicting a true evolution from a naive and confused boy to a tough and confident young man. Hunnam shines as the truly charismatic and often misguided Pete, who places integrity and loyalty above all else, who gives bear hugs to friends right after beating an adversary to a pulp. Leo Gregory is good as Bower, Pete's best friend and utterly weak-willed individual, and Forlani gives a poignant portrayal of a sister and mother caught up in the mayhem.

Green Street Hooligans is one of those works that appear out of nowhere and take the viewer by surprise. Through the prism of its unsavory subject matter, it examines concepts like family, friendship and honor, not veering into melodrama or preachiness for even a second. The film is a fascinating look at a sadistic sub-culture, one that paradoxically breeds closeness among its members just as much as it breeds unnecessary divisions among human beings.8/10

Weekly Review -- Let the mind games begin

Sucker Punch (2011) -- Billed as one of the hotly anticipated films of 2011, it was a surprise to many, including yours truly, when the latest Zack Snyder effort was promptly knocked out by critics and audiences alike. Labeled as sloppy, reckless and, worst of all, misogynistic, the film was dismissed and soon forgotten. Flawed though it is, Sucker Punch is undoubtedly a phantasm feast, with a unique story to match its nightmarish realms.

Sucker Punch (2011) -- Billed as one of the hotly anticipated films of 2011, it was a surprise to many, including yours truly, when the latest Zack Snyder effort was promptly knocked out by critics and audiences alike. Labeled as sloppy, reckless and, worst of all, misogynistic, the film was dismissed and soon forgotten. Flawed though it is, Sucker Punch is undoubtedly a phantasm feast, with a unique story to match its nightmarish realms.

**THIS REVIEW CONTAINS SPOILERS**

After her evil stepfather commits her to a mental institution, Babydoll (Emily Browning) has five days until she is subjected to a lobotomy. Desperate to escape, she loses herself in her imagination running wild, inventing steroid-fueled battlefields that she navigates with a group of fellow patients -- Sweet Pea (Abbie Cornish), Rocket (Jena Malone), Blondie (Vanessa Hudgens) and Amber (Jamie Chung) -- and a mentor (Scott Glenn). In order to get away, the women need to locate five essentials, but will they last long enough to beat the outside forces that keep closing in?

The problem with Sucker Punch is the contradictory method it utilizes to make its points. What purpose did the strip club story serve exactly? I would have enjoyed the multiple warrior fantasies that Babydoll experiences, but without the entire sleaze context. Come to think of it, it is funny how the previews had omitted that part. Was there not a way to link Babydoll's agony directly to these gorgeously disturbing worlds, their magnitude a polar opposite of her current circumstances? It even makes more sense than having the club as go-between, in my opinion. And no, the skimpy outfits do not help. We are supposed to be watching women fighting for their lives, not Barbie dolls doing a runway show. Also, what on Earth is going on with those names? Babydoll, Sweet Pea, Rocket... if the film is meant to be satirizing sexist entertainment, it constantly keeps turning on itself. However, that is precisely the reason why I never got the sense that the film was this big, threatening, anti-woman howl. It feels as though Snyder had intended to create an action fantasy with a feminist slant, but got distracted along the way by visions of pretty CGI landscapes and the boys-and-toys mentality. I do not even think that Snyder is the one to blame for the film ending up as a mash-up of dichotomies, since I keep imagining Hollywood (male) execs expanding their wallets and proportionally plunging the (female) actors' necklines deeper into chauvinist debt.

The performances are mostly compelling, but suffering from a hollow script. Browning is ethereal as Babydoll, who brandishes a sword just as easily as she pulls a trigger. Cornish gives a complex performance as Sweet Pea, a girl unaware of herself until tested, and Malone is memorable as Sweet Pea's sister, the often idealistic Rocket. Jon Hamm is excellent playing two very different roles, although he could have used more scenes, and Oscar Isaac's loathsome orderly Blue makes one's skin crawl.

A film like Sucker Punch is either a huge hit or a huge miss, since there is no middle ground when it comes to female empowerment. This is a theme that does not so much require grandiosity as it does finesse in presentations of its metaphorical value. Unfortunately, when intellectual depth and clarity is overpowered by eye candy shuffle, so is any significance that a particular work might have had. Sucker Punch has good intentions, but its thesis fades into a parody of itself through its own conflicted psyche, getting stuck in a wasteland between squandered potential and mixed messages.

6/10

Shame (2011) -- Addiction, in its many forms, contributes to the downward spiral of millions of people every day. Sometimes the locus of the urge is externalized, such as food or alcohol, and sometimes it is internalized, as in the case of sex or self-harm. In each instance, there is an inner void that triggers the behavioral pattern. This emptiness and the disastrous power that its consequences wield is the subject of Steve McQueen's sophomore film.

Shame (2011) -- Addiction, in its many forms, contributes to the downward spiral of millions of people every day. Sometimes the locus of the urge is externalized, such as food or alcohol, and sometimes it is internalized, as in the case of sex or self-harm. In each instance, there is an inner void that triggers the behavioral pattern. This emptiness and the disastrous power that its consequences wield is the subject of Steve McQueen's sophomore film. A Dangerous Method (2011) -- The human mind is a labyrinth of mysteries, each one more exciting than the last. Until medical professionals started revealing its riddles, people were not even sure how to view or treat mental illness. Throughout the centuries, most types of disorders were equated with personal rebellion and civil disobedience, with many patients having been placed in institutions and the key thrown away. The situation changed with Sigmund Freud's invention of psychoanalysis, a treatment that delved deep into repressed feelings and blocked memories, thereby beginning to solve the puzzles of the subconscious. David Cronenberg's A Dangerous Method takes a look at this process while examining the lives of the key players, namely Freud, his protégé Carl Jung and Sabina Spielrein, their mutual patient.

A Dangerous Method (2011) -- The human mind is a labyrinth of mysteries, each one more exciting than the last. Until medical professionals started revealing its riddles, people were not even sure how to view or treat mental illness. Throughout the centuries, most types of disorders were equated with personal rebellion and civil disobedience, with many patients having been placed in institutions and the key thrown away. The situation changed with Sigmund Freud's invention of psychoanalysis, a treatment that delved deep into repressed feelings and blocked memories, thereby beginning to solve the puzzles of the subconscious. David Cronenberg's A Dangerous Method takes a look at this process while examining the lives of the key players, namely Freud, his protégé Carl Jung and Sabina Spielrein, their mutual patient.